Anything Goes Pt.2

Eleanor Kane Neary’s approach should be seen in a wider context.

Charlotte Marie Horenberger was born in Chicago in 1915. Her father absconded from the family in the first year of her life and she lived in the north side of the city with her mother who bought her an upright piano and made her practice every day. This was simply a chore until her mother brought home a Victrola phonograph and 25 Irish records which very likely included discs by fiddlers such as Michael Coleman, James Morrison, and Paddy Killoran, early migrant stars versed in South Sligo stylings.

When her mother died in 1931 she moved to southside Chicago, where she lived with her aunt and finished her schooling. She marked this transition in life by changing her name to Eleanor Kane Neary and began playing at parish dances, weddings and social events. At one of these events she ran into Pat Roche, a young Irish dancer freshly arrived from Ireland and teaching in various parishes of the city.

Roche invited Eleanor to join a band he was putting together quickly to play at the Chicago World Fair which ran from 1933-34. An Irish American historian, Charles Fanning, has written several articles that touch on the cultural tensions of that fair and, in particular, the tensions between the official presence of the Irish Free State and the Irish American community.

The first, aiming to improve international trade and to demonstrate "high culture," was an exhibition of business, science, and the arts officially sponsored by the Irish Free State. The second, aiming above all to make money for its investors, was an "Irish Village," a commercial venture rooted in popular culture, and entirely American in conception and follow-through

An inventory of the Irish exhibition in the Travel and Transport building would trigger many people who have experienced a conservative Irish upbringing. It would include the reproductions of Celtic and early Christian jewellery, medals, claddagh rings, blackthorn sticks, indigenous minerals, embroidered napkins, worked leather and, for a mass, chalices, monstrances and ciboria. Among the books for sale was a recently commissioned translation of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, a prescient warning of what was to come in the fair itself as far as the Irish were concerned.

In May 1934 the Irish Village opened, an enterprise funded by Irish American investors who nurtured a vision that unended the virtuous and puritanical spirit of the Free State. Constructed on one of the main streets in the fair, the project sat between a ‘Midget Village’ and a reconstruction of Fort Dearborn, while a ‘Merrie England’ pavilion sat facing it. It’s launch invitation promised ‘the Irish Village will be an education; to Ireland a monument’. As Jekyll it stated there would be ‘Venerable ruins, rich art treasures, historic monuments, Old Abbeys and Shrines—a deft blending of the antique with the modern.’ And as Hyde it added that the ‘innocent amusement’ would include ‘Songs and music aplenty from the land that cradled the Irish race. Rollicking street scenes—a gay carnival spirit that will sweep you along in a whirl of excitement.’

Charle Fanning notes that

One contemporary account has it that "the Irish village ... started off with a naughty peep show next to the shrine of St. Brenda; and with girls in silk tights peddling shamrocks." In the run-up to opening day, the Irish Village Corporation had petitioned the fair's administration for permission to stage some bizarre attractions, among them a "Marine Spectacle," involving a mermaid "seen beneath the waters off the rocky coasts of Ireland"; a "Fortune Telling booth" illustrative of the "hundreds of fortune tellers throughout the 'Emerald Isle"'; and, on a slightly different tack, a tableau presentation of "The Lord's Last Supper."

The Irish Village was attacked immediately by the more conservative elements of the Irish community who pointed to the Chicago nightclub ambience of the main hall and the titillating content of the historical tableau. Ave Maria (‘a family magazine devoted to the honor of the Blessed Virgin) called for a boycott as ‘the performances misrepresent Irish Life, and are a travesty on the race.’[1] By June the Village was bankrupt and after a hasty takeover by new backers it reopened with a genteel upgrade of its content (though it did advertise a new harp quartet and a roller skating act…).

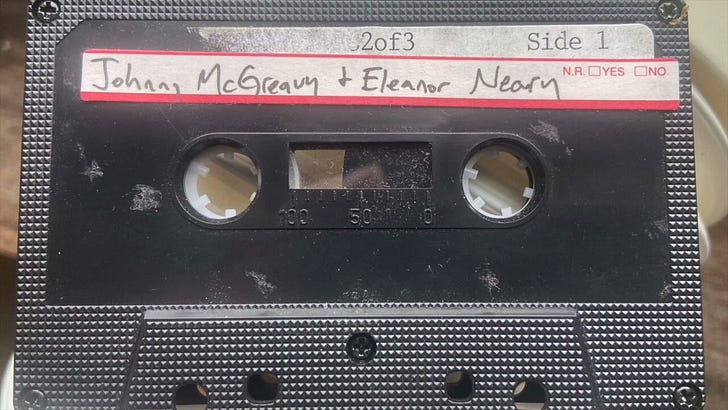

It was in this reformed landscape that Pat Roche's Harp and Shamrock Orchestra was invited to play seven days a week. It was immediately recognised that their music avoided parodies, burlesque or sentimental caricatures. There was an awareness of the developing ceili sound in Ireland combined with all the plugged in energy of 20th century Chicago – it swings hard and this was two years before Count Basie took his band to the same city to record their first sides. Decca acknowledged the power of Roche’s band and recorded four tunes in October 1934 and another six in November 1935. In that same month they also recorded two more with Johnny McGreevy accompanied by Eleanor and one track with her alone on the 15th.

Eleanor Kane Neary’s career mutates after this date. Demand for Irish band and dances seems to have collapsed and Irish music went underground until the 1960s. Eleanor though kept playing and her house (she had married an Irish fiddler, Jimmy Neary, in 1939) became a vital hub for musicians passing through the city, for local sessions with Johnny McGreevy, Joe Shannon and others. There were poorly paid gigs at Irish dances and fairs, the occasional tribute (Fiddler Liz Carroll points to “the time she played in a small hall in the Bronx, around 1957–58. There were two Steinway pianos and each of the musicians there played a tune with Eleanor.” Charles Fanning adds that ‘The participants included Roscommon piper Andy Conroy and three great Sligo fiddlers, Andy McGann, Lad O’Beirne, and Paddy Killoran, all of whom had played with Michael Coleman. In addition, Ed Reavy paid a lasting compliment by composing “Eleanor Kane’s Reel,” a perennial favorite that’s been recorded by everyone from Reavy himself to De Danaan.’)

If that 1935 recording for Decca was a landmark in Irish music her second great achievement was more nebulous but just as important. She not only kept the music alive in her house but inspired a series of younger people to continue the tradition – fiddler Liz Carroll, accordionist Jimmy Keane, dancer Michael Flatley, and pianist Marty Fahey among others. There are also constant rumours of an albums worth of recordings that may yet be released and even this week an hour’s worth of home recordings with Johnny McGreevy surfaced on YouTube.

[1] Ave Maria, July 7,1934, pp. 22-23. The piece also contains this illustrative anecdote: "The Irish Village at the Chicago World's Fair, we have been told, is in the hands of non-Christians who are doing their best to out-do the Streets of Paris of last-year fame. One person who visited there tells us that while he was in the village a sweet colleen appeared upon the stage and sang a beautiful little song with some such title as "A Little Piece of Lace My Mother Wore." It really thrilled the hearts of the audience, but when she was encored and repeated the chorus, she was accompanied by eight chorus girls who, to the disgust of everyone present, wore nothing more than a piece of lace. Most of the audience left the place at once."