Skirting the Event Horizon

In an article entitled ‘Untreatable: The Freudian Act and its Legacy’ the psychoanalyst Tracy McNulty discusses the physical impact of the patient’s encounter with an analyst.[1] It moves beyond the explicit narratives of the psychoanalytic process to a more intangible act of transmission between the two. To do this she hones in on one particular moment in the process: ‘My point of departure is the mechanism of the Pass, which Lacan introduced in 1967 as a means of tracking and accounting for action of the object a, the object-cause of desire that animates the analyst’s act.’ Lacan believed that in an anylsis the analyst is struck both psychically and physically by something that is being transferred from the patient. This indefinable ‘something’ leaves impressions on the analyst and McNulty describe this effect as akin to that of a black hole in space ‘which cannot be perceived directly, but is known only by the way it warps space-time—the object of psychoanalysis is an object we know solely by its effects’.[2]

She argues that this reference to black holes and their warping of space-time is a useful index to the intangible presence and effect of an act in the psychoanalytic process. And it is this impact that is central to the process of ‘the pass’ in which a patient recounts the trajectory of their analysis to two ‘passeurs’ who in turn transmit this testimony after six months to a cartel of analysts, gathered specifically to respond and make a judgement on the analysis. McNulty describes how the indefinable thing that is transmitted tends to be a physical gesture or symptom that manifests unwittingly in the passeurs[3]

This notion of an intangible emotion or idea having a physical impact on a recipient is not a new one. It has a particular history in both religion and art, sometimes reaching another level when it concerns an art workart work within a religion. The Shaker religion, Santeria, Sufi whirling dervishes and Sioux ghost dancers all point to an intimate relationship between the body, ecstatic states and divine communication. In his 1972 novel, Mumbo Jumbo, Ishmael Reed posits a nation riven with plague called Jes Grew, a viral jazz bug that unleashes a radical sensual response in all its victims:

The door opens to a main room of the church which has been converted into an infirmary. About 22 people lie on carts. Doctors are rushing back and forth; they wear surgeon’s masks and white coats. Doors open and shut.

“What’s the situation report, doc?” the Mayor asks.

“We got reports from down here that people were doing “stupid sensual things,” were in a state of “uncontrollable frenzy,” were wriggling like fish, doing something called the “Eagle Rock” and the “Sassy Bump”; were cutting a mean “Mooche,” and “lusting after relevance.”

“It’s nothing we can bring into focus or categorize; once we call it 1 thing it forms into something else.

No man. This is a psychic epidemic, not a lesser germ like typhoid yellow fever or syphilis. We can handle those. This belongs under some ancient Demonic Theory of Disease.”

The novel is now considered an early classic of afro-futurism and is recognised as a direct influence on works as diverse as Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) and George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic collective discography (1970-present).[1]

A more overlooked aspect of the book lies in its’ multiple dedications:

To my grandmother

Emma Coleman Lewis.

And to

Clarence Hill, proprietor of

Libra’s on East 6th Street

between A & B

and also for

George Herriman, Afro-American,

who created Krazy Kat.

George Herriman had been considered a white artist throughout his life and for nearly 30 years after his death (1944) this belief still held sway. It was only in 1971 that a sociologist Arthur Asa Berger came across Herriman’s New Orleans birth certificate which listed him as ‘colored’ while the 1880 census for the city categorised his parents as ‘mulatto’.

Berger’s discoveries have slowly rippled through the comic world and even more slowly through the wider world where comics remain underexplored despite the great advances of recent years. Berger was also a pioneer in tackling the sexual complexities of Krazy Kat and in an essay titled ‘Of Mice and Men: An Introduction to Mouseology Or, Anal Eroticism and Disney’ he compares and contrasts Disney’s Mickey Mouse and Herriman’s Ignatz, coming down firmly on the side of the latter: ‘If Mickey was the instrument of … a ‘rage to order’, then Ignatz was the instrument of what we might describe as a ‘love of disorder and chaos…of a messy world of mixed-up characters.’[2] [4]

It is this queer, anarchistic spirit in Krazy Kat that appeals to Berger:

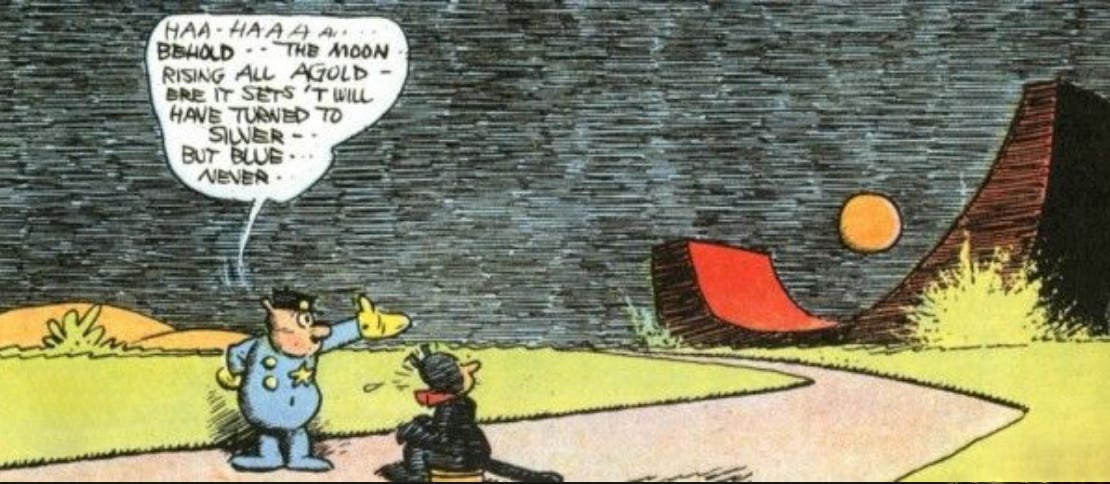

The mouse I love is Ignatz Mouse, Herriman’s malevolent, anti-authoritarian, incorrigible hero who heaved a brick at a lovesick Krazy Kat for thirty years…The situation in Krazy Kat is complicated in the extreme. Ignatz loves throwing bricks at Krazy, who takes the bricks as signs of love…There is a third major protagonist, Offisa Pupp, who loves Krazy and hates Ignatz. Pupp spends his life trying to protect Krazy from Ignatz, and arresting him and throwing him in jail when he does ‘crease’ Krazy with a brick…There are, I would argue, two important themes in this strip: the triumph of illusion over reality (as shown by Krazy’s belief that the bricks are signifiers of love) and anti-authoritarianism (as shown by Ignatz’s brick throwing).[5] [3]

There are also, as has slowly become apparent, two important undercurrents running through the Krazy Kat strip – race and gender. These subjects were never explicitly addressed, and it is only with later investigation into Herriman’s life that they began to emerge. Ishmael Reed’s brief but momentous nod to Krazy at the start of his novel points to a whole new reading of the comic strip. It is not just art and jazz that propels the plague in Mumbo Jumbo but black art specifically that is seen as transgressive. Krazy Kat, then, is work at the forefront of American culture (published by Randolph Hearst’s newspaper syndicate which controlled 28 papers across the nation in the 1920s). The comic was converted into films and it inspired all kinds of merchandise. It was also the subject of a jazz ballet in 1922, composed by John Alden Carpenter. Closer to the world of Mumbo Jumbo, Herriman’s character also inspired the tune ‘Krazy Kat’ by Frankie Trumbauer (with Bix Beiderbecke) while Cleon Throckmorton, the most in-demand set designer of the Jazz Age opened the Krazy Kat club which morphed into a speakeasy during the prohibition years:

The club's name derived from the androgynous title character of a comic strip that was popular at the time, and this namesake communicated that the venue catered to clientele of all sexual persuasions, including polysexual and homosexual patrons. Due to this inclusive policy, the secluded venue became a rendezvous spot for Washington, D.C.'s gay community who could meet without fear of exposure. By 1922, the Kat's libertine denizens were known for their unapologetic embrace of free love ("unrestricted impulse"), and municipal authorities publicly identified the venue as a den of vice.[6]

If Jes Grew was a psychic epidemic that impacted physically on the general American population then Krazy Kat was a potent variant, a strain with a proven record.

It's clear then that the ambiguities of Herriman’s creation did not pass unnoticed by its readers though the artist did not talk about the strip’s content in any depth publicly. Part of the pleasure of the strip lay in the codes and ciphers it employed on every level of content. As Cleon Throckmorton astutely divined, there was a joyful deviance in the ‘unnatural’ loves of the three main protagonists: cross species and cross gender loves that left the characters conflicted, unrequited and unrepentant. The cat, Krazy, is open to love and embraces their desires. The dog, as a staunch enforcer of the law, barely allows his desires to surface. Ignatz the mouse, married with three children, is the most complex– his bricks acting as both signals of love and anger, aimed at the subject he finds himself bound to everyday.

Tracey McNulty’s description of the object-cause of desire in psychoanalysis as ‘a black hole—which cannot be perceived directly, but is known only by the way it warps space-time’ provides a way of understanding the coded signals emanating from Krazy Kat. The strip’s readers were adept at reading the sparse hints scattered by Herriman over the 33 years of the Kat’s existence – the sporadic change of pronouns from one day to the next, sometimes even between adjacent frames; the deeply embedded meditations on colour; gnomic allusions to tragic events and skewed, queer, plots. The perceived shallowness of the comic genre allows the artist a great deal of latitude to smuggle in more pointed material. In May 1944, for instance, a brown weasel finds himself considered a poor risk by an insurance company and learns that as a white weasel he would be ‘worth a fortune’. A quick trip to the beauty parlour results in a ‘bleached’ weasel who can now pass as white. One of the last strips published a month after Herriman’s death, it seems reasonable to assume this plot might contain an acerbic reference to his own final arrangements.

This persistent need to speculate is a key element in the experience of reading Krazy Kat. Nothing is as it seems, everything is in flux. One of the most striking examples of this is in the strip’s background landscapes. One panel may be set in daylight, in the second darkness has fallen only for light to reappear in the third. Meanwhile a mesa and palm tree that set a scene in one part of a story might morph into pyramids or dinosaurs further down the page.

Language too is profoundly unstable. Often the dialogue is a kaleidoscope of dialects and idioms. Shakespearean English, Yiddish, Navajo sayings, minstrelsy scripts and colloquial Americanisms all rub shoulders promiscuously. It is not surprising to find that ee cummings and Gertrude Stein were among the most prominent fans of Krazy Kat.

Meanwhile beyond those hot jazz homages by Trumbauer and Biederbecke lies a vast field of songs performed mostly by Krazy accompanied by his banjo. His best known and often repeated song, ‘There Is a Happy Land’, was a hymn. The lyrics, published in 1838, were written by a Scottish schoolmaster Andrew Young though it was later set to a tune arranged by Leonard P. Breedlove. The theme is ambiguous, inviting us to a happy land that transpires to be the afterlife:

Come to this happy land,

Come, come away;

Why will you doubting stand,

Why still delay?

O we shall happy be

When, from sin and sorrow free,

Lord, we shall live with thee,

Blest, blest for aye.

This is the blues multiplied and deepened into resignation that this world is not going to provide the tolerance or joy we need. And yet, under the multiple masks of the comic, this observation is persistently overlooked. It is, after all, a cartoon cat playing a banjo while a fiery mouse launches a brick at his head. Every frame is brimming with unease and unspeakable pains. Krazy Kat ran daily for thirty-three years, repeating the same plot each day, out-Becketting even Samuel Beckett.[7] This soundtrack, unspooling over decades, weaves a corona of melancholy and unrequited love around one of the most visible comics in America.

With no explicit statements forthcoming from Herriman, his readers are compelled to decipher the warped ‘space-time’ phenomena around the comic strip and to act as passeurs of the experience we imbibe as we read it. And as passeurs, the readers have carried the spirit of Krazy Kat surreptiously into contemporary culture. Unlike Mickey and Disney, Ignatz and Krazy have infiltrated society in a studiously non-capitalist way. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Herriman’s work became a key inspiration for the emerging underground comix scene: Robert Crumb, Chris Ware and Art Spiegelman were devoted fans. From the modernists (Picasso, De Kooning) to the Beat poets and contemporary philosophers (Umberto Eco), Krazy Kat resonated while rockabilly and blues labels showered equal honour on the comic. As Ishmael Reed’s revelation permeated minds and critiques of sexuality and gender expanded, Herriman’s characters found more knowing readers.

In many ways, it is the hermeneutic void at the centre of his work that provides a space for alternative dimensions to flourish. In 1937 Boyden Sparkes, a journalist researching a biography of a Hearst newspaper editor, came to visit Herriman who told him: ‘most people who like that work of mine are people who supply their own ideas – there is no story to it. There is no story, no characters, purely my own invention….’[8]

[1] Tracy McNulty, “Untreatable: The Freudian Act and its Legacy”in Agon Hamza and Frank Ruda, editors, “Jacques Lacan: Psychoanalysis, Politics, Philosophy and Science.” Special issue of Crisis and Critique, Volume 6, issue 1 (April 2019), 227-251.

[2] McNulty, “Untreatable”, 227.

‘Jacques Lacan, in his seminar “The Analytic Act,” suggests that the patient’s act is not something the analyst can know, interpret, or anticipate, but something by which he is “struck” both psychically and in his body, where it leaves its traces or impressions. The act leaves effects in the real; it acts upon the body, and not upon the understanding alone. What “strikes” the analyst in the act—as distinct from the “acting out” that often characterizes the analysand’s way of relating to the analyst, for example as an object of love or aggression—is what Lacan calls the object (a), the “object-cause of desire” that acts in and through the subject. Like a black hole—which cannot be perceived directly, but is known only by the way it warps space-time—the object of psychoanalysis is an object we know solely by its effects. Because the object-cause of desire is a purely mental object that does not properly speaking “exist,” it cannot be perceived, sensed, or known empirically. Instead, it must create a path for itself in the world, through the subject’s act’

[3] [3] McNulty, “Untreatable”, 228-229.

‘The Pass involves the passant, the candidate who addresses her request to the School, and two passeurs, or witnesses, to whom the passant speaks about his analysis. These passeurs are in turn responsible for transmitting that testimony to a jury of analysts, who meet as a cartel and formulate a response: either nomination of the passant as an Analyst of the School, or no nomination. Yet the Pass is concerned not primarily with what the passant has managed to say about her analysis, but with something that exceeds the signifier, and that therefore passes through the body… It is not an object of conscious observation or recording, but instead something that is at once transmitted by a body and received by a body, depositing itself in the bodies of the two passeurs without their knowledge.

While giving my testimony, there were several occasions on which I leaned forward in my chair, my body almost parallel to the ground, and put my head in my hands: an attitude that felt very foreign to me, but which I nevertheless felt strangely compelled to adopt .’

[4] Arthur Asa Berger, “Of Mice and Men: An Introduction to Mouseology Or, Anal Eroticism and Disney” in Gay People, Sex, and the Media, Eds. Michelle A. Wolf and Alfred P. Kielwasser, (Philadelphia: Haworth Press, 1991), 155-166.

[5] Berger, “Of Mice and Men”, 161-162.

[6] Wikipedia entry on the Krazy Kat Klub, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Krazy_Kat_Klub

[7] ‘For over thirty years, George Herriman’s Krazy Kat comic strip featured the gender-ambiguous title cat singing strangely poetic love lyrics to Ignatz Mouse. Ignatz would respond by flinging bricks at Krazy Kat’s head, and Offissa Pupp, who absolutely adored Krazy Kat, would arrest Ignatz, which apparently made no difference. Through two world wars and the Depression, the same arc replayed thousands of times against a strange Arizona dreamscape.’

[8] Michael Tisserand, Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White, (New York: Harper Collins, 2016), 398.

This essay was first published in Queereal Secretions: Artistic Research as Exquisite Practice, eds Coutts, Nicky and Rogers, Henry, Glasgow, 2023.